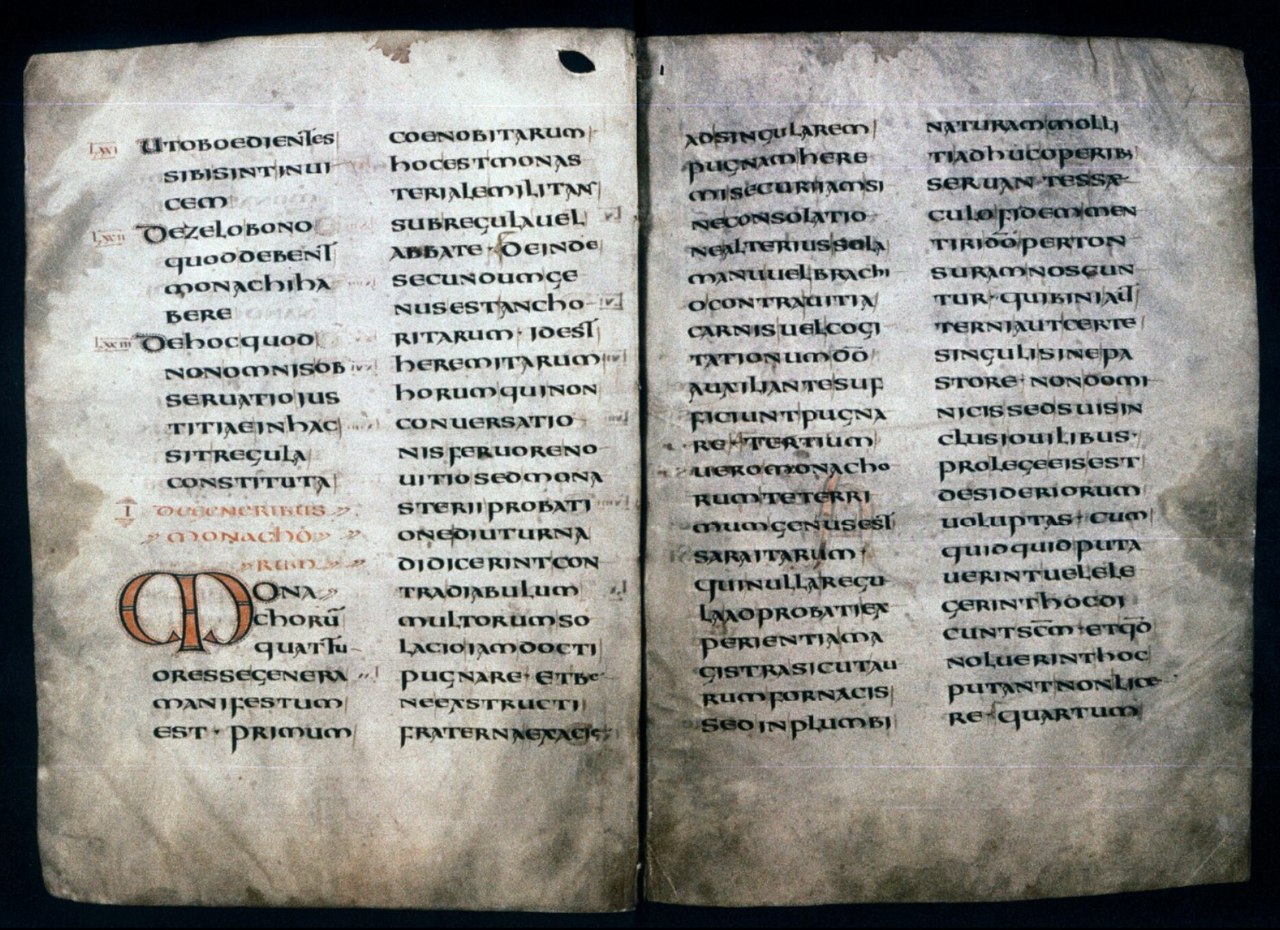

These excerpts were taken from the 1935 translation of the Rule by Leonard J. Doyle and edited by Dom Cuthbert Butler. 1 If you are interested in seeing the full text, Project Gutenberg has it available in several formats here: St. Benedict’s Rule for Monasteries.2

The Rule is set up in chapters, but each chapter is then broken into readings that are to be read three times a year. The dates that you see indicated in these excerpts are indicating these three readings. These readings were done while the monks ate, and also included

Prologue

. . .

Jan. 7 — May 8 — Sept. 7

And so we are going to establish a school for the service of the Lord. In founding it we hope to introduce nothing harsh or burdensome. But if a certain strictness results from the dictates of equity for the amendment of vices or the preservation of charity, do not be at once dismayed and fly from the way of salvation, whose entrance cannot but be narrow. For as we advance in the religious life and in faith, our hearts expand and we run the way of God’s commandments with unspeakable sweetness of love. Thus, never departing from His school, but persevering in the monastery according to His teaching until death, we may by patience share in the sufferings of Christ and deserve to have a share also in His kingdom.

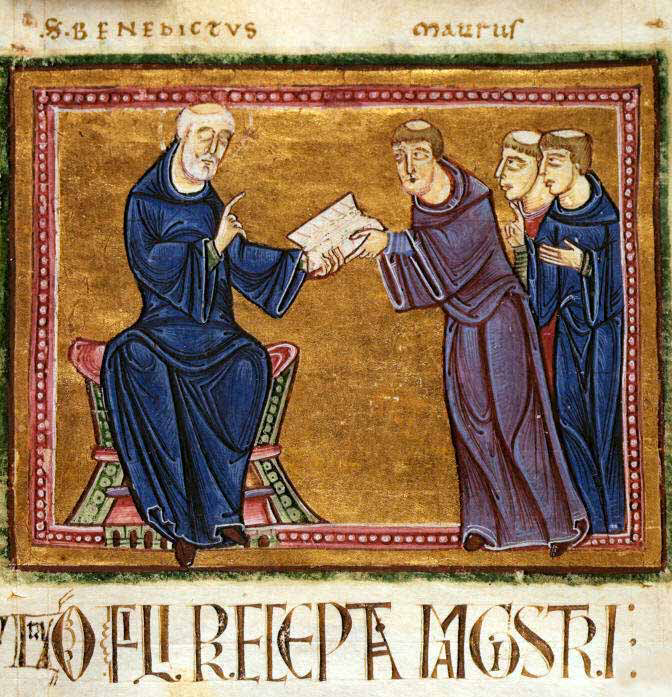

Chapter 1: On the Kinds of Monks

Jan. 8 — May 9 — Sept. 8

It is well known that there are four kinds of monks. The first kind are the Cenobites: those who live in monasteries and serve under a rule and an Abbot.

The second kind are the Anchorites or Hermits: those who, no longer in the first fervor of their reformation, but after long probation in a monastery, having learned by the help of many brethren how to fight against the devil, go out well armed from the ranks of the community to the solitary combat of the desert. They are able now, with no help save from God, to fight single-handed against the vices of the flesh and their own evil thoughts.

The third kind of monks, a detestable kind, are the Sarabaites. These, not having been tested, as gold in the furnace, by any rule or by the lessons of experience, are as soft as lead. In their works they still keep faith with the world, so that their tonsure marks them as liars before God. They live in twos or threes, or even singly, without a shepherd, in their own sheepfolds and not in the Lord’s. Their law is the desire for self-gratification: whatever enters their mind or appeals to them, that they call holy; what they dislike, they regard as unlawful.

The fourth kind of monks are those called Gyrovagues. These spend their whole lives tramping from province to province, staying as guests in different monasteries for three or four days at a time. Always on the move, with no stability, they indulge their own wills and succumb to the allurements of gluttony, and are in every way worse than the Sarabaites. Of the miserable conduct of all such men it is better to be silent than to speak.

Passing these over, therefore, let us proceed, with God’s help, to lay down a rule for the strongest kind of monks, the Cenobites.

Chapter 2: What Kind of Man the Abbot ought to Be

. . .

Jan. 11 — May 12 — Sept. 11

Therefore, when anyone receives the name of Abbot, he ought to govern his disciples with a twofold teaching. That is to say, he should show them all that is good and holy by his deeds even more than by his words, expounding the Lord’s commandments in words to the intelligent among his disciples, but demonstrating the divine precepts by his actions for those of harder hearts and ruder minds. And whatever he has taught his disciples to be contrary to God’s law, let him indicate by his example that it is not to be done, lest, while preaching to others, he himself be found reprobate, and lest God one day say to him in his sin, “Why do you declare My statutes and profess My covenant with your lips, whereas you hate discipline and have cast My words behind you?” And again, “You were looking at the speck in your brother’s eye, and did not see the beam in your own.”

Jan. 12 — May 13 — Sept. 12

Let him make no distinction of persons in the monastery. Let him not love one more than another, unless it be one whom he finds better in good works or in obedience. Let him not advance one of noble birth ahead of one who was formerly a slave, unless there be some other reasonable ground for it. But if the Abbot for just reason think fit to do so, let him advance one of any rank whatever. Otherwise let them keep their due places; because, whether slaves or freemen, we are all one in Christ and bear an equal burden of service in the army of the same Lord. For with God there is no respect of persons. Only for one reason are we preferred in His sight: if we be found better than others in good works and humility. Therefore let the Abbot show equal love to all and impose the same discipline on all according to their deserts.

. . .

Chapter 4: What are the Instruments of Good Works

Jan. 18 — May 19 — Sept. 18

- In the first place, to love the Lord God with the whole heart, the whole soul, the whole strength.

- Then, one’s neighbor as oneself.

- Then not to murder.

- Not to commit adultery.

- Not to steal.

- Not to covet.

- Not to bear false witness.

- To respect all men.

- And not to do to another what one would not have done to oneself.

- To deny oneself in order to follow Christ.

- To chastise the body.

- Not to become attached to pleasures.

- To love fasting.

- To relieve the poor.

- To clothe the naked.

- To visit the sick.

- To bury the dead.

- To help in trouble.

- To console the sorrowing.

- To become a stranger to the world’s ways.

- To prefer nothing to the love of Christ.

Jan. 19 — May 20 — Sept. 19

- Not to give way to anger.

- Not to nurse a grudge.

- Not to entertain deceit in one’s heart.

- Not to give a false peace.

- Not to forsake charity.

- Not to swear, for fear of perjuring oneself.

- To utter truth from heart and mouth.

- Not to return evil for evil.

- To do no wrong to anyone, and to bear patiently wrongs done to oneself.

- To love one’s enemies.

- Not to curse those who curse us, but rather to bless them.

- To bear persecution for justice’ sake.

- Not to be proud.

- Not addicted to wine.

- Not a great eater.

- Not drowsy.

- Not lazy.

- Not a grumbler.

- Not a detractor.

- To put one’s hope in God.

- To attribute to God, and not to self, whatever good one sees in oneself.

- But to recognize always that the evil is one’s own doing, and to impute it to oneself.

Jan. 20 — May 21 — Sept. 20

- To fear the Day of Judgment.

- To be in dread of hell.

- To desire eternal life with all the passion of the spirit.

- To keep death daily before one’s eyes.

- To keep constant guard over the actions of one’s life.

- To know for certain that God sees one everywhere.

- When evil thoughts come into one’s heart, to dash them against Christ immediately.

- And to manifest them to one’s spiritual father.

- To guard one’s tongue against evil and depraved speech.

- Not to love much talking.

- Not to speak useless words or words that move to laughter.

- Not to love much or boisterous laughter.

- To listen willingly to holy reading.

- To devote oneself frequently to prayer.

- Daily in one’s prayers, with tears and sighs, to confess one’s past sins to God, and to amend them for the future.

- Not to fulfil the desires of the flesh; to hate one’s own will.

- To obey in all things the commands of the Abbot, even though he himself (which God forbid) should act otherwise, mindful of the Lord’s precept, “Do what they say, but not what they do.”

- Not to wish to be called holy before one is holy; but first to be holy, that one may be truly so called.

Jan. 21 — May 22 — Sept. 21

- To fulfil God’s commandments daily in one’s deeds.

- To love chastity.

- To hate no one.

- Not to be jealous, not to harbor envy.

- Not to love contention.

- To beware of haughtiness.

- And to respect the seniors.

- To love the juniors.

- To pray for one’s enemies in the love of Christ.

- To make peace with one’s adversary before the sun sets.

- And never to despair of God’s mercy.

These, then, are the tools of the spiritual craft. If we employ them unceasingly day and night, and return them on the Day of Judgment, our compensation from the Lord will be that wage He has promised: “Eye has not seen, nor ear heard, what God has prepared for those who love Him.”

Now the workshop in which we shall diligently execute all these tasks is the enclosure of the monastery and stability in the community.

Chapter 5: On Obedience

Jan. 22 — May 23 — Sept. 22

The first degree of humility is obedience without delay. This is the virtue of those who hold nothing dearer to them than Christ; who, because of the holy service they have professed, and the fear of hell, and the glory of life everlasting, as soon as anything has been ordered by the Superior, receive it as a divine command and cannot suffer any delay in executing it. Of these the Lord says, “As soon as he heard, he obeyed Me.” And again to teachers He says, “He who hears you, hears Me.”

Such as these, therefore, immediately leaving their own affairs and forsaking their own will, dropping the work they were engaged in and leaving it unfinished, with the ready step of obedience follow up with their deeds the voice of him who commands. And so as it were at the same moment the master’s command is given and the disciple’s work is completed, the two things being speedily accomplished together in the swiftness of the fear of God by those who are moved with the desire of attaining life everlasting. That desire is their motive for choosing the narrow way, of which the Lord says, “Narrow is the way that leads to life,” so that, not living according to their own choice nor obeying their own desires and pleasures but walking by another’s judgment and command, they dwell in monasteries and desire to have an Abbot over them. Assuredly such as these are living up to that maxim of the Lord in which He says, “I have come not to do My own will, but the will of Him who sent Me.”

. . .

Chapter 6: On the Spirit of Silence

. . .

Therefore, since the spirit of silence is so important, permission to speak should rarely be granted even to perfect disciples, even though it be for good, holy, edifying conversation; for it is written, “In much speaking you will not escape sin,” and in another place, “Death and life are in the power of the tongue.”

For speaking and teaching belong to the master; the disciple’s part is to be silent and to listen. And for that reason if anything has to be asked of the Superior, it should be asked with all the humility and submission inspired by reverence.

But as for coarse jests and idle words or words that move to laughter, these we condemn everywhere with a perpetual ban, and for such conversation we do not permit a disciple to open his mouth.

Chapter 7: On Humility

. . ..

Jan. 26 — May 27 — Sept. 26

The first degree of humility, then, is that a person keep the fear of God before his eyes and beware of ever forgetting it. Let him be ever mindful of all that God has commanded; let his thoughts constantly recur to the hell-fire which will burn for their sins those who despise God, and to the life everlasting which is prepared for those who fear Him. Let him keep himself at every moment from sins and vices, whether of the mind, the tongue, the hands, the feet, or the self-will, and check also the desires of the flesh.

. . .

Feb. 3 — June 4 — Oct. 4

The sixth degree of humility is that a monk be content with the poorest and worst of everything, and that in every occupation assigned him he consider himself a bad and worthless workman, saying with the Prophet, “I am brought to nothing and I am without understanding; I have become as a beast of burden before You, and I am always with You.”

Feb. 4 — June 5 — Oct. 5

The seventh degree of humility is that he consider himself lower and of less account than anyone else, and this not only in verbal protestation but also with the most heartfelt inner conviction, humbling himself and saying with the Prophet, “But I am a worm and no man, the scorn of men and the outcast of the people. After being exalted, I have been humbled and covered with confusion.” And again, “It is good for me that You have humbled me, that I may learn Your commandments.”

. . .

Chapter 23: On Excommunication for Faults

Feb. 28 (29) — June 30 — Oct. 30

If a brother is found to be obstinate, or disobedient, or proud, or murmuring, or habitually transgressing the Holy Rule in any point and contemptuous of the orders of his seniors, the latter shall admonish him secretly a first and a second time, as Our Lord commands. If he fails to amend, let him be given a public rebuke in front of the whole community. But if even then he does not reform, let him be placed under excommunication, provided that he understands the seriousness of that penalty; if he is perverse, however, let him undergo corporal punishment.

. . .

Chapter 29: Whether Brethren Who Leave the Monastery Should Be Received Again

Mar. 6 — July 6 — Nov. 5

If a brother who through his own fault leaves the monastery should wish to return, let him first promise full reparation for his having gone away; and then let him be received in the lowest place, as a test of his humility. And if he should leave again, let him be taken back again, and so a third time; but he should understand that after this all way of return is denied him.

Chapter 30: How Boys Are to Be Corrected

Mar. 7 — July 7 — Nov. 6

Every age and degree of understanding should have its proper measure of discipline. With regard to boys and adolescents, therefore, or those who cannot understand the seriousness of the penalty of excommunication, whenever such as these are delinquent let them be subjected to severe fasts or brought to terms by harsh beatings, that they may be cured.

. . .

Chapter 33: Whether Monks Ought to Have Anything of their Own

Mar. 11—July 11—Nov. 10

This vice especially is to be cut out of the monastery by the roots. Let no one presume to give or receive anything without the Abbot’s leave, or to have anything as his own—anything whatever, whether book or tablets or pen or whatever it may be—since they are not permitted to have even their bodies or wills at their own disposal; but for all their necessities let them look to the Father of the monastery. And let it be unlawful to have anything which the Abbot has not given or allowed. Let all things be common to all, as it is written, and let no one say or assume that anything is his own.

But if anyone is caught indulging in this most wicked vice, let him be admonished once and a second time. If he fails to amend, let him undergo punishment.

. . .

Chapter 39: On the Measure of Food

Mar. 18 — July 18 — Nov. 17

We think it sufficient for the daily dinner, whether at the sixth or the ninth hour, that every table have two cooked dishes, on account of individual infirmities, so that he who for some reason cannot eat of the one may make his meal of the other. Therefore let two cooked dishes suffice for all the brethren; and if any fruit or fresh vegetables are available, let a third dish be added.

Let a good pound weight of bread suffice for the day, whether there be only one meal or both dinner and supper. If they are to have supper, the cellarer shall reserve a third of that pound, to be given them at supper.

But if it happens that the work was heavier, it shall lie within the Abbot’s discretion and power, should it be expedient, to add something to the fare. Above all things, however, over-indulgence must be avoided and a monk must never be overtaken by indigestion; for there is nothing so opposed to the Christian character as over-indulgence, according to Our Lord’s words, “See to it that your hearts be not burdened with over-indulgence.”

. . .

Chapter 40: On the Measure of Drink

Mar. 19 — July 19 — Nov. 18

“Everyone has his own gift from God, one in this way and another in that.” It is therefore with some misgiving that we regulate the measure of other men’s sustenance. Nevertheless, keeping in view the needs of weaker brethren, we believe that a hemina of wine a day is sufficient for each. But those to whom God gives the strength to abstain should know that they will receive a special reward.

If the circumstances of the place, or the work, or the heat of summer require a greater measure, the Superior shall use his judgment in the matter, taking care always that there be no occasion for surfeit or drunkenness. We read, it is true, that wine is by no means a drink for monks; but since the monks of our day cannot be persuaded of this, let us at least agree to drink sparingly and not to satiety, because “wine makes even the wise fall away.”

But where the circumstances of the place are such that not even the measure prescribed above can be supplied, but much less or none at all, let those who live there bless God and not murmur. Above all things do we give this admonition, that they abstain from murmuring.

. . .

Chapter 48: On the Daily Manual Labor

Mar. 28 — July 28 — Nov. 27

Idleness is the enemy of the soul. Therefore the brethren should be occupied at certain times in manual labor, and again at fixed hours in sacred reading. To that end we think that the times for each may be prescribed as follows.

From Easter until the Calends of October, when they come out from Prime in the morning let them labor at whatever is necessary until about the fourth hour, and from the fourth hour until about the sixth let them apply themselves to reading. After the sixth hour, having left the table, let them rest on their beds in perfect silence; or if anyone may perhaps want to read, let him read to himself in such a way as not to disturb anyone else. Let None be said rather early, at the middle of the eighth hour, and let them again do what work has to be done until Vespers.

[And then follow several paragraphs describing how the hours for work, reading etc. will change with the seasons.]

. . .

Chapter 53: On the Reception of Guests

Apr. 4 — Aug. 4 — Dec. 4

Let all guests who arrive be received like Christ, for He is going to say, “I came as a guest, and you received Me.” And to all let due honor be shown, especially to the domestics of the faith and to pilgrims.

As soon as a guest is announced, therefore, let the Superior or the brethren meet him with all charitable service. And first of all let them pray together, and then exchange the kiss of peace. For the kiss of peace should not be offered until after the prayers have been said, on account of the devil’s deceptions.

. . .

After the guests have been received and taken to prayer, let the Superior or someone appointed by him sit with them. Let the divine law be read before the guest for his edification, and then let all kindness be shown him. The Superior shall break his fast for the sake of a guest, unless it happens to be a principal fast day which may not be violated. The brethren, however, shall observe the customary fasts. Let the Abbot give the guests water for their hands; and let both Abbot and community wash the feet of all guests. After the washing of the feet let them say this verse: “We have received Your mercy, O God, in the midst of Your temple.”

In the reception of the poor and of pilgrims the greatest care and solicitude should be shown, because it is especially in them that Christ is received; for as far as the rich are concerned, the very fear which they inspire wins respect for them.

Apr. 5 — Aug. 5 — Dec. 5

Let there be a separate kitchen for the Abbot and guests, that the brethren may not be disturbed when guests, who are never lacking in a monastery, arrive at irregular hours. Let two brethren capable of filling the office well be appointed for a year to have charge of this kitchen.

. . .

The guest house also shall be assigned to a brother whose soul is possessed by the fear of God. Let there be a sufficient number of beds made up in it; and let the house of God be managed by prudent men and in a prudent manner.

On no account shall anyone who is not so ordered associate or converse with guests. But if he should meet them or see them, let him greet them humbly, as we have said, ask their blessing and pass on, saying that he is not allowed to converse with a guest.

. . .

Notes

1. Benedict of Nursia, abbot of Monte Cassino, and Leonard J. Doyle Translator. St. Benedict’s Rule for Monasteries. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1948.

2. Benedict of Nursia, abbot of Monte Cassino and Leonard J. Doyle translator. St. Benedict’s Rule for Monasteries. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1935. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/50040/50040-h/50040-h.html

Except where otherwise noted, Excerpts from St. Benedict’s Rule by Nicole V. Jobin is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0